The meaning and use of ‘race riot’ in British newspapers

The historian Kieran Connell (2024) has written about the ‘inability […] of the media […] to put an accurate label’ on what happened during riots in 1958 in Nottingham and Notting Hill, asserting that rather ‘than “white riots” or “racist riots”, it was “race riots” – a term more open to interpretation – that became conventional.’ This article outlines the history of that label in British newspapers.

Existing literature

This is not the first publication dealing with that subject. There is an extensive literature on riots in Britain (for example, Flett (2015), Moran (2020), Rowe (1998)). The historiography also contains many works on race riots. This article does not engage with that entire output. Instead, it highlights with selected studies to indicate the thinking about this subject.

In their pioneering study on Liverpool riots in 1919, May and Cohen (1974) have discussed the difficult nature of the ‘race riot’ concept. Holmes (1975) has done so too, reviewing race in relation to riots in Nottingham and Notting Hill in 1958, but Miles (1984) has noted that the 1958 riots were political and ideological conflicts, and that specific ideologies ensured that the idea of race came to be used to interpret them. Recently, Hilliard (2022) has re-examined the questioned relation between the Notting Hill riots and racism.

Writing about disturbances in Middlesbrough in 1961, Panayi (1991) has stated that these events can be described as race riots and fit into a pattern of previous attacks in Britain on population groups formed by immigrants and their descendants. In addition to hostility towards immigrants, Panayi has also stressed local factors that lead to the Middlesbrough disturbances as well as nation-wide youth violence, without which there would not have been a riot.

Farrar (2002) has claimed that disturbances in Leeds in 2001 were not race riots, but violent urban protests by racialised British men. However, Kanol (2010) has called other riots in northern English cities like Oldham, Burnley and Bradford in 2001 race riots. Concentrating on causes, Solomos (2011) has found that factors that shaped disturbances in 2011 included race, but he has argued against generalisations about its role, which should be viewed within a range of issues such as policing, deprivation and exclusion.

Historians in the USA have also questioned the meaning and use of the term ‘race riots’. Keenan (2016) has maintained that many US incidents of civil unrest labelled as race riots must be understood as manifestations of racial cleansing. Ray (2022) has noted that before the 1960s US race riots were popularly understood as white violence against black and other coloured.

The existing literature also contains studies of newspaper discourse on such disturbances. Following his analysis of editorials in the British press about disorders in 1985, particularly The Sun and Daily Mail, Van Dijk (1987, 1989, 1991) has concluded that in relation to racism and riots ideological structures systematically appeared in categorisation, argumentation, organisation, rhetorical devices and lexical styles of the press. Similarly, Criado (2005) has analysed how disturbances in Oldham in 2001 were reported by, among other papers, The Sun, Daily Mail, The Independent and The Times. Both Van Dijk and Criado have emphasised the papers’ characterisation of participants in civil disorder and a tendency to label coloured people negatively as potential rioters, holding them responsible for the unrest, and differentiate a minority of troublemakers among otherwise innocent white people.

In short, the existing literature is fragmented and the concept of ‘race riots’ remains controversial. While this article cannot provide a comprehensive history of this phenomenon, it complements the existing literature by outlining the changes in the use and meaning of ‘race riot’ in British newspapers.

Sources and methodology

Within the scope of this article it is unfeasible to examine the entire newspaper output.

From the daily newspapers that appeared throughout this period and are available to this author in a digital format suitable for analysis, The Times is chosen. Published in London, it is one of Britain’s oldest and most influential papers. Although its editorial views are independent, The Times can be seen as a paper of record and epitome of the British establishment (for a history of The Times see Woods and Bishop (1983)). The paper itself is available via The Times Digital Archive in Gale Primary Sources, an online, full-text facsimile of the paper, intended to provide every page from 1785.

During the period under review, traditional newspapers like The Times evolved but also had to compete with the new popular press. In 1900 the reading public in Britain predominantly consumed local or regional newspapers, but after 1921 national popular papers, such as the Daily Mail, overtook the local and regional press (for overviews of the history of the British newspaper press, see Bingham and Conboy (2015), Griffiths (1992)). Newspapers also sought to strengthen their position in relation to other media. When broadcast news services were expanding, and the television provided respectable and entertaining content, the gaps for the press lay in supplying greater detail and in-depth investigation. Traditional papers such as The Times also adapted their editorial policies, for example creating well-illustrated and handsomely designed space for subjects that were thought to interest the public. Journalists also altered their writing styles to describe events in clear and direct but imaginary and meaningful terms (an example of a writing manual for journalists is Evans (1972)). The style change and the constant race against deadlines altered their language use, popularising certain words or phrases and their meanings, and using them as labels to denote a subject (the language use in newspapers has been discussed by Bell (1991), Fairclough (1995), Kibble (2002)).

This article compares The Times to titles in the British Newspaper Archive (BNA). In 2025, this resource contained pages from over 1,700 newspapers published in the UK from the 18th century to the present day. The BNA is continuously growing. At first, it incorporated publications from before 1900 and cities such as Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds, along with local titles from London boroughs and smaller places. Then, it started adding material from a wider variety of papers from 1900 onwards, for example the Daily Express and Daily Mirror. As a result, newspapers aimed at local and regional audiences and popular papers feature prominently in the BNA.

The two digital collections have been searched online. Unfortunately, at present the technology available to this author still causes imprecision and the statistics reproduced in the quantitative analysis of this article contain errors and remain incomplete. Therefore, the purpose of that analysis is not providing exact and comprehensive numbers but revealing trends in word use. The qualitative analysis then applies critical methods to examine specific articles in The Times and what appeared in other newspapers. This enables the synthesis of information in a chronologically ordered narrative.

Meanings and undertones

Online lexicons provide various meanings of ‘race riot’. The Historical Thesaurus of English records its use from 1880. The Online Etymology Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary also list this first use in Britain, coming from American English, and describe it as a riot resulting from racial hostility or tension. The Cambridge Dictionary gives two meanings: a violent fight between people of different races; and a situation in which people from a particular ethnic group protest violently about something.

The term ‘race riot’ has connotations. ‘Race’ has various meanings, including originally the sense of shared kin, family, descent, occupation or nationality, but from the 19th century increasingly and eventually predominantly the sense of shared physical characteristics, such as skin colour. On the issue of skin colour, the Online Etymology Dictionary points out that in mid-20th century US publications ‘race’ meant ‘negro’. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary states that the use of ‘race’ referring to physical traits was for many years applied in scientific fields such as physical anthropology, with race differentiation being based on such qualities as skin colour, but advances in the field of genetics in the late twentieth century found no biological basis for races in this sense of the word. For this reason, according to the dictionary, the concept of distinct human races has little scientific standing today, apart from a sociological designation, identifying a group sharing some outward physical characteristics and commonalities of culture and history.

The affective meaning of ‘riot’, in the sense of civil disorder or disturbance, is historically negative. The Historical Thesaurus records it under ‘Moral evil: Profligacy, dissoluteness or debauchery’. Modern lexicons emphasise the violent nature of riots.

Quantitative analysis

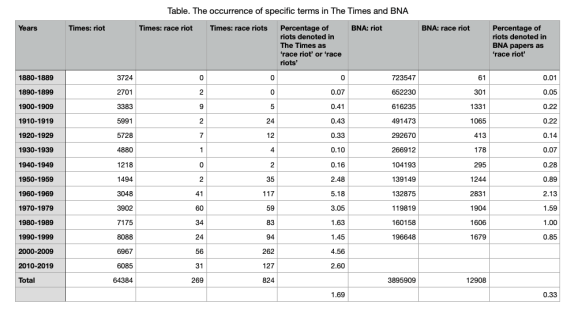

This table shows that in the period 1880-2019 The Times used ‘riot’ 64,384 times. Although it often appeared in clusters, for example more than once per report or in more articles on one day, the word was used on average 463 times a year. It was therefore a subject that readers of this newspaper frequently saw if they read the entire paper every day. This does not mean a riot occurred in Britain every day, The Times also reported on riots abroad or discussed in parliament. In comparison, the BNA papers used ‘riot’ 3,939,056 times between 1880 and 1999, indicating that readers of a BNA paper were also frequently confronted by an article on riots.

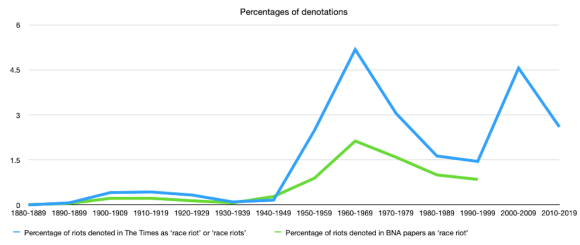

Only small percentages of these ‘riot’ articles were on ‘race riots’. A search in The Times Digital Archive shows 269 results for ‘race riot’ from 1890, a separate search for ‘race riots’ brings up 824 results from 1900. Apparently, after initially favouring the single form, editors, journalists and letter writers in The Times as well as foreign correspondents and agency reporters were more likely to apply the plural form of this term after 1910, apart from the decade 1970-1979. A similarly separated search is impossible in the BNA, as ‘race riot’ is there also included in finds for ‘race riots’, while the BNA search for ‘race riot’ also includes false finds, for example ‘racing riot’ or ‘race. Riot’. Under this proviso, the percentages of articles using ‘riot’ that were on ‘race riots’, have been reproduced in the image below.

This image shows that before 1949 the percentage of ‘riots’ denoted in The Times as ‘race riot’ or ‘race riots’ remained under one percent, with the peak in 1910-1919, corresponding with the peak of ‘riot’ in 1910-1919. After 1949 the percentage in The Times rose sharply to well above one percent, peaking in 1960-1969. The percentage of ‘riots’ denoted in BNA papers as ‘race riot’ stayed under one percent until 1960, with the peak in 1950-1959. From 1949 the BNA percentage rose to 1960-1969, after that it dropped but remained well above the pre-1950 figures. The image also illustrates that after 1890, except for the decade from 1940 to 1949, The Times published relatively more articles on ‘race riots’ than BNA papers.

In short, ‘riot’ appeared on average daily in The Times and frequently in BNA papers. Only small percentages of these articles were about ‘race riots’, with higher proportions in The Times than BNA papers. Peaks in the usage of ‘race riot’ occurred during the decades 1910-1919, 1950-1959 and 1960-1969.

Qualitative analysis

On 19 December 1888 the term ‘race riot’ first appeared in a BNA newspaper. That day the Orkney Herald, and Weekly Advertiser and Gazette for the Orkney & Zetland Islands reported ‘Race riots in Mississippi’. Probably using a newsfeed from New York, the paper mentioned a ‘conflict’ between white people and ‘negroes’ in Wahalak. Reports on the incident were confusing, also with US papers such as Detroit Free Press and Knoxville Daily Tribune describing it as a ‘war’. Claims were made that whites had sought revenge after a car accident involving a white and a black driver. There was also uncertainty about the number of fatalities, varying from 2 to 12 whites and up to 150 blacks. The next use of ‘race riot’ in a BNA paper occurred on 6 February 1890, when the Ayr Advertiser reported: ‘A serious race riot has (says a New York telegram) occurred at Morgan, Georgia.’ The disturbance involved, according to the Advertiser, 7,000 persons, ‘most of them negroes […]’ It followed the lynching of a 15-year-old black boy, who was accused of murdering a 9-year-old white girl.

On 20 October 1890 The Times first used ‘race riot’, writing about violence against Italian immigrants in New Orleans. The paper reported that the US city appeared ‘to be on the eve of a sanguinary race riot’ after it had been ‘ascertained’ that following their murder of the chief of police, the ‘“Mafia” secret society planned to murder a number of other officials.’ Nineteen Italians were arrested, 11 of them were lynched after a mob stormed the prison. The Times wrote: ‘The public feeling is very strong against the Italian community. [A] steamer with [1,000 Italian immigrants] is now coming up the river. Some persons advocate resistance to [their] landing.’

On 3 January 1891 ‘race riot’ appeared again in The Times, but now the paper discussed the ‘negro question’ in the USA. This was followed on 6 August 1907 with a report on a New York ‘race riot’:

between whites and negroes, in which more than a thousand persons were engaged. Two white men were taken to hospital mortally injured. The trouble began with a dispute between a white and a negro over the payment of a wager. The whites used baseball bats as weapons, and the negroes used razors, while negro women climbed on the roofs of the houses and pulled bricks from the chimneys, which they threw upon the white men in the street.

The Times later reported regularly on ‘race riots’ in the US, for example on 2, 3 and 4 June 1921 in Tulsa, where during a ‘Day and Night of Terror’ about 100 people were killed, ‘mostly negroes, and in addition it is feared that as many more negroes are lying beneath the smouldering ruins of their houses.’ The 1921 Tulsa events were widely reported in Britain, for example by the Dundee Evening Telegraph (1 June), Daily Herald, Daily News and Scotsman (all 2 June) and Sheffield Daily Telegraph (4 June).

Later, The Times reported more US ‘race riots’, for instance on 9 February 1926 and 21 March 1927. However, the paper did not apply the label ‘race riot’ to disturbances in Britain until 27 August 1958, when it wrote about ‘the recent race riot in Nottingham’. This means that the 1910-1919 peak in the percentage of unrest reported in The Times as ‘race riots’ was related to reports about riots abroad, not Britain.

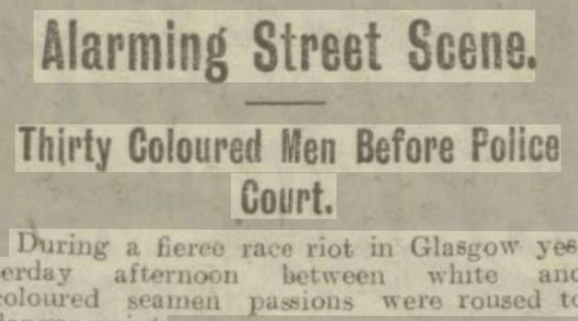

In contrast, BNA papers had from 1919 used the label to denote disturbances in Britain. One of the first outbreaks during that year was reported on 24 January in the Dundee Evening Telegraph as a ‘Fierce Race Riot’ in Glasgow. The violence broke out over competition for work, as it was thought that black sailors were given preference in signing on for a ship about to sail. This caused resentment among white sailors, who also believed that the black men accepted lower wages. It resulted in a scuffle, during which a black sailor was reported to have fired a revolver, injuring a white man in the neck, and a ‘white’ contingent charged the black men. According to the report, the white mob was armed, some with guns. Bottles and stones were thrown at the retreating black sailors and the windows of their lodging house.

More violence from white crowds was directed at black and coloured workers in 1919, leading to deaths, injuries and vandalised property in South Shields, Salford, London, Hull, Newport, Barry, Liverpool and Cardiff (overviews of these events have been provided by Evans (1980), Jenkinson (2009)).

The Daily News reported on 6 June a ‘Race Riot’ in Liverpool. The paper related how prior to this outbreak ‘racial feeling’ had been running ‘high [in the city] for some time past.’ That had resulted in a ‘fatal battle’ between Liverpool’s black population and ‘Russians and Swedes’. Whites were ‘chasing negroes’. A black man was ‘thrown into a dock and drowned’. Fourteen others were wounded.

On 8 June 1919 the Sunday Pictorial reported ‘fierce racial riots’ in Newport. It was said that the outbreak had been stoked by relationships between black men and ‘white girls’. The violence spread down the Welsh coast to Cardiff, with houses being torched and three persons killed. It reportedly started when a black man began firing on the police which infuriated a white crowd, who attacked black and coloured men and hunted them for hours. More shooting was heard in the Welsh city, with volleys being fired in the streets and from houses.

The 1919 Welsh disturbances got national exposure in papers like Derby Daily Telegraph (12 June), Belfast Telegraph (13 June), Aberdeen Press and Journal and Dundee Courier (both 13 June) and The Times (13 and 14 June). On 13 June a correspondent of the Morning Post compared the unrest in Glasgow, Liverpool and Cardiff to colonial immigration problems in Australia and Canada and drew a parallel to lynching in the USA: ‘[…] the burning of three negroes at the stake in the United States, a horror which was witnessed by hundreds of approving men and women.’ The journalist stated ‘the coloured races and our white race cannot live together on terms of equal freedom […] It is the insuperable difference that has to be recognised.’

The 1919 disturbances in Wales echoed unrest in 1911 when, in the wake of an unsuccessful miners’ strike, a wave of violence swept through the western valleys of South Wales. Property – mostly owned by Jewish shopkeepers, pawnbrokers and landlords – was attacked. Although non-Jewish tradesmen were also assaulted and The Times wrote on 24 August 1911 that a ‘spirit of indiscipline ran riot’ with ‘bottle-flinging experts’ battering ‘an alien colony’, there was little doubt about the riots being mostly aimed at Jews. Among the ‘rioters’ were reportedly fun-seeking hooligans as well as respectable working people, such as colliers and their wives, who may have feared having to pay debts to traders who had advanced credit. Five years later Wales witnessed further disturbances. On a Sunday afternoon in 1916 ‘Arabs’ and ‘negroes’ were targeted in Tiger Bay after ‘a young girl, daughter of respectable parents, was found in a dazed condition in a doorway, after having been missing for a week.’ The wider background to the incident was revealed with the suggestion in the Daily Mail on 6 October that the victims were to blame for showing off their social and economic successes: ‘[The] coloured population of Cardiff profited by high wages, almost daily take country rides in motorcars and carriages, and foreign boarding-house keepers are buying houses in suburbs.’

While no such ‘riots’ in Britain were reported during the interwar period, the issue returned after 1945 with the growing arrival of black and coloured immigrants, for instance from the West Indies.

In 1956 Godfrey Elton, former Under-Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs, spoke in the House of Lords (Hansard, 20 November 1956) about the settlement of West Indians, which caused ‘a problem’ that if not dealt with, would cause more ‘race riots’. He referred to the 1919 disturbances in Liverpool and said that a ‘race riot’ had taken place there as recent as 1949. Elton probably meant 1948, when the Liverpool Echo wrote on 2 and 26 August 1948 about three nights of disturbances, involving ‘white and coloured men’, which resulted in dozens of arrests and ‘six coloured men and one white man’ appearing in the magistrate’s court, after the police dispersed a crowd in the ‘coloured quarter’ of Liverpool and had been ‘showered with bricks […] from windows […]’. The incident was also reported in the Nottingham Journal(3 August), Aberdeen Press and Journal (4 August) and Nottingham Evening Post (10 August). During the same year, according to local papers such as the South London Observer (22 July and 5 August), disturbances took place in London, where hundreds of white men attempted to force their way into a Deptford lodging house where around 40 black immigrant workers resided, possibly after a street-fight. The police intervened and following two nights of clashes, a third drew a crowd of 1500 but passed peacefully. In several other labour hostels, including the Causeway Green hostel in Birmingham (Birmingham Gazette,10 August), tensions between black and white workers exploded.

Ten years after the Liverpool ‘race riot’ of 1948 disturbances struck Nottingham. The violence was ignited in a pub in the St Ann’s district of the city. Early reports in local papers, such as the Nottingham Evening Post (and Nottingham Evening News, both 25 August 1958), claimed the riot was initiated by black men: ‘The fight started after a young married woman, 21-year-old blonde Mrs. Mary Lowndes […] had been punched in the back by a coloured man. It happened just after closing time.’ The woman told the Post:

I was leaving the St. Ann’s Well Inn with my husband […] when one of the black men hit me in the back […] The next thing I knew was that my husband was being punched from one side of the road to the other by three coloured men. I heard bottles being smashed. Everyone was screaming and shouting.

The husband, a 23-year-old miner, came away, according to his wife, with only slight bruises to the face: ‘He knew how to take care of himself, otherwise the blacks might have killed him.’

Another white man needed 37 stitches after he was slashed ‘from ear to ear’ with a razor by a ‘coloured man’ outside the pub. A local woman who had taken a stabbed white man into her house said: ‘Coloured men were running all over the place, howling and brandishing knives. They were chasing everyone.’ The reports contained more stories of ‘darkies’ and a ‘negro’ attacking white people. A week later, trouble brewed again in St Ann’s. However, that weekend there were few black people on the street and the white mob turned on itself. The next week homes of black people were attacked, bricks and bottles were thrown, and a mob chased black men, assaulting five. The police stopped the violence.

The Nottingham Evening Post reported the first disturbance as a ‘racial clash’ and ‘racial battle’. The Nottingham Evening News spoke of ‘racial warfare’. The Times on 1 September called it a ‘race clash’, the weekly magazine Time and Tide of 6 September said ‘so-called race riots’ and the Daily Mirror had on 25 August declared a ‘race riot’.

Perhaps the fight in the St Ann’s Well Inn that reportedly started the disturbance was not caused by racial hostility but constituted a dispute between drunken people or a row between disgruntled neighbours – an ordinary pub brawl that turned into a riot. However, the Nottingham Evening Post in its reports of 25 August quoted St Ann’s residents who said a feeling of resentment between whites and blacks had been simmering for weeks and the ‘war boiled over when a group of Teddy Boys beat up a few coloured men.’ A local butcher also blamed Teddy Boys: ‘In a pub last week I saw one darkie being needled by a group of whites so much that he got fed up with it. When he said something to them they took him outside to report him to a policeman for starting a fight.’ The Assistant Chief Constable of Nottingham told a press conference that the fighting had flared up as ‘coloured people’ reprised previous incidents when ‘some of their number’ had been attacked by white men. In contrast, according to The Times (26 August, 1 and 2 September), Captain Athelstan Popkess, long-serving Chief Constable of the Nottingham City Police, said:

This was not a racial riot. The coloured people behaved in an exemplary way by keeping out of the way. Indeed they were an example to some of the rougher elements. The people primarily concerned were irresponsible Teddy Boys and persons who had had a lot to drink.

As the first Nottingham crowd was dispersed, disturbances broke out in London when a group of young men toured Notting Hill and Shepherd’s Bush. According to The Times of 26 August 1958, they allegedly assaulted ‘coloured men’. The next weekend, violence in the capital started when about 100 white youths armed with sticks, iron bars and knives gathered near an underground station in North Kensington, apparently after rumours that a Jamaican man had assaulted his white wife. The youths threw bricks at police cars, and a man was slashed across the throat. Subsequently, wrote The Times on 1 September, fights between ‘whites’ and ‘coloured’ people erupted.

The Daily News of 2 September 1958 provided details. It mentioned Seymour Manning, a Jamaican who lived in Birmingham and was in London to visit relatives. While walking down Bramley Road he stopped to ask for directions. Three young men sprang out of a small van and attacked him. Pursued by a crowd of men and women, Manning ran into a greengrocer’s shop. ‘They are going to kill me,’ he cried. The grocer’s daughter bolted the door. She ‘thought the crowd were going to break in and get him out.’ The mob threw bottles at the shop and windows were smashed.

Reports in the Daily News (2 September), The Times (2, 3, 4 and 5 September) and Daily Telegraph (3 September) showed how the violence spread throughout London. In Ladbroke Grove, another black man was assaulted, being ‘kicked in the back as he left the Underground’. In Barr Road, a group of men smashed ‘a basement window with an iron-bar’ and threw a lit paraffin lamp into the room. In Uxbridge Road ‘a gang of Teddy boys beat-up a coloured man and his German girlfriend.’ Meanwhile, in Harrow Road, coloured people stood on the roof of a café, owned by a black man, ‘showering milk-bottles down on white passers-by’. As the police intervened – there were ‘threatening crowds’ – they were ‘jeered by white and coloured youths, and broken bottles were thrown.’ This led to dozens of arrests of young and middle-aged men, including blacks. Later that night the police skirmished again with white youths.

What exactly caused the Nottingham and London disorders remains unclear. Although the contemporary evidence is impressionistic, it suggests that the troublemakers were not solely Teddy Boys or young hooligans. On 8 December 1958 The Times quoted a speaker at a conference of the Consultative Committee for the Welfare of Coloured People in Nottingham: ‘1958 saw a distinct hardening in the attitude of the British people to the coloured communities among them.’ The press was to bear some responsibility for this deterioration:

If what happened [in Nottingham and London] had involved the Irish it would have been termed ‘drunken brawl’. If it had involved sailors or Teddy boys it would have been another Saturday night scrap. Because it involved coloured people the only term the Press could use was ‘race riot’.

If what happened [in Nottingham and London] had involved the Irish it would have been termed ‘drunken brawl’. If it had involved sailors or Teddy boys it would have been another Saturday night scrap. Because it involved coloured people the only term the Press could use was ‘race riot’.

West Indians formed not the only immigrant group who were attacked during what were reported in 1961 as ‘race riots’ in Daily Mail (21 and 22 August), The Times (21 August) and Evening Gazette (19 August). In that year disorder broke out in Middlesborough after a ‘local lad’ had been fatally stabbed by an ‘Arab’. The next day, wrote the Yorkshire Post of 21 August, a crowd threw stones and bottles at the Taj Mahal cafe, owned by an English woman and her Pakistani husband. The rioters then set fire to a table in the cafe, assaulted adjoining properties, attacked a general dealer’s shop owned by an ‘Arab’ and turned upon the police. Violence in several parts of Middlesborough lasted for days, mostly aimed at Pakistanis. Panayi (1991) has shown that local factors, such as personal hostility between the café-owners and a criminal, played a role in the disturbance. As in Nottingham in 1958, the Middlesborough Chief Constable of did not regard the disturbance ‘a major race riot’ and one of his Detective Inspectors asserted in the Daily Mail of 22 August: ‘We are satisfied that there was no actual black versus white racial conflict as such.’

Similar disturbances in Leeds in 1969 with whites attacking Pakistanis were reported in The Times of 29 July. In ‘the immigrant quarter’, following the fatal stabbing of a local teenager during the weekend, the police made 23 arrests after 1,000 people had taken part in a disturbance. On a second night of violence an ‘angry mob of several hundred people massed outside a Pakistani-owned café […] screaming and chanting: “Wogs out” […] As a bottle was hurled through the plate glass window of an Asian café, people cheered.’ Apparently, the crowd was ‘incensed’ by news that early on that day a 71-year-old woman had been attacked at her home nearby, which the police said bore ‘no connection’ to the weekend stabbing. A South-Asian man had been charged with murdering the teenager, and two other South-Asian ‘labourers’ were accused of aiding and abetting murder and possessing an offensive weapon.

So far, the UK disturbances between 1919 and 1969, which were reported as ‘race riots’ in British newspapers, involved mainly white attacking black and coloured people and colliding with the police, with blacks defending themselves or striking back. After 1969 ‘race riot’ acquired another meaning. In 1980 it was first used to label a British disturbance, when The Times reported on 3 April: ‘Police battled with hundreds of black youths in Bristol yesterday in a riot that started after a raid on a club.’ Hundreds of policemen went into the St Paul’s district of that city ‘shortly before midnight to re-establish law and order after eight hours of rioting by about 300 black youths.’ The West Indians had overturned police cars, burnt a bank and a post office, pelted firemen with bricks and bottles, and looted shops after police officers had raided the Black and White Club, allegedly a den for illegal drinking and drugs misuse. A black men told The Times it was ‘the start of a war between the police and the black community.’ Community-relations officials said that the eruption of violence probably resulted from friction which had been evident for several years.

A minister, who was driving in the area at the time, said: ‘It was not a race riot […] Colour has nothing to do with this. I think it was a question of authority, and reaction to authority rather than a question of colour.’ Politicians took a similar view. Following a statement by Home Secretary William Whitelaw in the Commons (Hansard, 3 April 1980), William Waldegrave MP emphasised ‘that the disturbances were not a race riot in the simplistic sense of those words. It was not a matter of one community attacking another.’ Tony Benn MP said: ‘Clearly it was not a race riot […]’ The Home Secretary agreed, declaring: ‘[…] it was not in any sense a race riot.’ The Secretary’s statement was reported in The Times on 3 and 5 April 1980 as: ‘[…] not a race riot in the sense that black people were attacking white people.’ And: ‘It is not in a simplistic sense of the word a race riot. It is not a matter of one community fighting another.’ BNA papers reported such opinions. The Bristol Evening Post of 3 April 1980 quoted a community worker who said it was not a ‘race riot’: ‘It was a riot of depression. It is this depression that exploded.’ Similarly, on 3 April 1980 the Daily Express described the ‘ugly scene’ as ‘not so much a race riot [but] a spontaneous eruption of violence on the part of the black community.’

An editorial in The Times of 7 April 1980 qualified these denials and thus introduced a new interpretation of ‘race riot’:

Some have taken consolation in the opinion that what happened in Bristol was not a race riot. That needs qualification […] the affair was racial in as much as it is traceable to a concentration of people of West Indian origin in that place, to the social fabric of their surroundings, and to the disproportionately poor prospects they have cause to expect for themselves, especially the young among them. A significant proportion of black youth there and elsewhere are estranged from a society which bears hardly upon them; and they have, in the colour of their skins, the strongest of all promptings to feel self-consciously racial about it.

British newspapers now attributed a new, additional meaning to ‘race riot’. The Liverpool Echo on 3 April 1980 indicated the origins of the additional meaning when it reported under the title ‘Angry ghetto’: ‘The Bristol flare-up has not come as a surprise to immigrant leaders and social workers in the area. For years they have been predicting that the festering tension in the deprived slums would explode.’

The word ‘ghetto’ in the Liverpool paper referred to areas in US inner cities where American blacks were concentrated. During the 1960s and 1970s large disturbances broke out in these ghettos. This coincided with increasing usage of ‘race riot’ in British newspapers. As shown in the quantitative analysis, peaks in the percentage of reports of ‘riots’ denoted as ‘race riots’ appeared in 1960-1969 in The Times and BNA papers.

The disturbances in the USA were different from earlier unrest. For instance, unrest in 1967 in Detroit, Michigan, was one of more than 150 disorders across the country in the summer of that year, in which black people vented their anger about what they regarded as inequality and oppression. The direct cause in Detroit was a police raid on an illegal black pub. Less than a year later, the murder of Martin Luther King led to a US-wide wave of similar disturbances. The unrest did not subside. In 1969, for example, The Times on 28 June reported a ‘race riot’ in an industrial town north of Indianapolis, which was said to have begun after a group of whites burnt a cross and Black Panthers injured policemen with shotguns.

The US events were widely reported in Britain. A search for ‘race riot’ in the BNA finds 548 articles in 1967. A similar search in The Times shows six results for the same. The article of 21 July in The Times, ‘Race Riot Danger in Britain’, quoted a ‘warning of race riots in Britain tomorrow’ in a British government-supported report that said: ‘If England is not to be the scene of race riots the time for action is now, tomorrow may be too late.’

The Bristol disorder of 1980 thus resembles the US disturbances of the 1960s and 1970s. It may even have been influenced by the news about the US events. As a result, ‘race riot’ now meant either an incident where one population group attacked another, mostly white against black and coloured people, including immigrants and their descendants, or disorder from people with black and coloured skins.

The Bristol disturbance was repeated later – often at a much larger scale – in other English cities and towns, for instance in 1981, 1985 and 2011. In April 1981, following police intervention in a stabbing of a black boy, police officers were attacked in Brixton, London, possibly as it was believed the police had stopped and questioned the stabbed boy, rather than help him. Hundreds of black youths turned on the police and the disturbance lasted for days, with people injured, vehicles destroyed and shop premises burned, damaged and looted. Disturbances also took place elsewhere in the capital. The Times did not report this as a ‘race riot’ and several BNA papers stated opinions that this disturbance was not such an event; the Sunday Mirror of 19 April 1981 called it ‘an antipolice riot’. However, the Daily Express of 13 April 1981 was adamant: ‘The urgent lessons of Brixton […] WHEN the American race riots appeared on British television screens in the 1970s, we thought they could never happen here. Now they have – with a vengeance.’

A few months later, similar events occurred in Toxteth, Liverpool, where after a perceived heavy-handed arrest of a black man, police were attacked by blacks with petrol bombs and paving stones. The unrest also affected other Merseyside districts, Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, Bradford, Halifax, Blackburn, Preston, Wolverhampton, Newcastle, Nottingham, Derby, Leicester, Southampton and Portsmouth. The Times on 6 July 1981 reported the event in Toxteth ‘was not a race riot in the context of Brixton […]’, mostly as white and black youths fought the police together. Some BNA papers concurred, but others, including the Daily Express on 4 and 6 July, spoke of ‘race riots’.

In 1985, the ‘Broadwater Farm riot’ in London was related to the death of an immigrant woman and it followed a week after another black woman had been shot by the police. Some newspapers blamed the black population for the riot. On 30 September 1985, The Sun claimed ‘The blacks must act’ and on 8 October 1985 the Daily Mail‘s editorial was titled ‘The choice for Britain’s blacks’. In 2011, violence broke out in London after a black man was shot fatally dead by police in Tottenham. Subsequently, disorder took place in cities and towns across England, including Birmingham, Bristol, Coventry, Liverpool, Manchester, Nottingham, Derby and Leicester.

Other immigrant groups and their descendants also got involved in such disturbances, for example in 2001 in Leeds, where hundreds of young men of South-Asian descent clashed with the police after the allegedly wrongful arrest of a South-Asian man. In the Harehills area of the city the youths erected a barricade of burning washing machines and furniture, looted from a second-hand shop. Cars were burnt, a shop was set alight, police officers, journalists and onlookers were injured. During the same year, a disorder ensued when South Asians in Bradford confronted extremist right-wing groups, culminating in the stabbing of a South-Asian man and a South-Asian man firebombing the Manningham Labour Club. Meanwhile in Oldham, hundreds of South-Asian youths used petrol bombs, attacked a pub and the offices of a local newspaper and battled the police. The Times reported on 17 and 18 April 2001 that the police first said the ‘riot’ was ‘not racial’ but then admitted that ‘race did play part’ in the event.

Fighting also occurred between groups of immigrants and their descendants. On 27 May 2006 The Times wrote that three young South-Asian men were found guilty of murdering a young black man. The trio were said to be members of a much larger South-Asian gang that chased the man at the height of ‘riots’ in 2005 in Birmingham: ‘[…] one of the first cases to receive national attention that has portrayed racism as something other than a black and white issue.’ What exactly happened is unclear. Perhaps the unrest arose from tensions between West-Indian and South-Asian groups living in and around the Lozells area of the city, which may have been fuelled by economic rivalry and the activity of opposing gangs. The spark that ignited the violence was thought to have been an unsubstantiated rumour about a gang rape of a Jamaican teenager by a group of Pakistani men.

The newspaper reporting of ‘race riots’ continues to the present day. For example, during the protests at hotels housing asylum-seekers. In 2024, after rumours that a migrant killed three girls in Southport, anti-immigration riots spread from across Britain. The Daily Express wrote on 12 August 2024: ‘Britain’s Commonwealth future in jeopardy thanks to race riots’. On 14 June 2025 The Guardian commented on ‘race riots’ against the local ‘migrant population’, which had started in Ballymena, Northern Ireland, ‘ostensibly triggered by the arrest of two boys, reported to be of Romanian origin, accused of sexually assaulting a teenage girl.’ The white rioters drove out dozens of Romanian and Bulgarian families and ‘other foreigners’. A month later, an asylum-seeker assaulted a teenage girl and woman in Epping. The culprit was quickly arrested, found guilty and convicted, but large rallies across Britain turned violent against immigrants residing in hotels and community-based accommodation, and were labelled as ‘race riots’ on websites of various newspapers such as the Daily Mail (24 and 25 July), Daily Express (2 August) and The Times (23 August).

Conclusion

This article has outlined the history of the term ‘race riot’ in British newspapers. It has found that ‘race riot’ was an Americanism that was applied as a label in British newspapers from 1888 to various disturbances with different characteristics and dissimilar causes. However, it always had undertones, because of the negative loading of the word ‘riot’ and the association of ‘race’ with black or coloured people.

In 1888 the label ‘race riot’ was attached by British newspapers to a disturbance in the USA, in which whites attacked black people. In 1890 it referred to a US disorder, in which whites attacked white immigrants. From 1919 papers started to report disturbances in Britain as ‘race riots’. No ‘race riots’ in Britain were reported during the interwar period, but the issue returned after 1945 with the settlement of immigrants with non-white skin colours. The label was applied in 1948 to disturbances in Liverpool involving white and coloured men, in 1958 to unrest in Nottingham, possibly initiated by black men, and to disturbances in London with white attacks on black people, who sometimes fought back, and in 1961 to riots in Middlesborough where whites attacked South Asians.

From 1980 ‘race riot’ – as used for disturbances in Britain – acquired an additional meaning. This started in reports on disturbances in Bristol, where blacks attacked white property and the police. Politicians denied it was a ‘race riot’ in the sense of one population group attacking another. The Times qualified this denial and introduced the new interpretation of ‘race riot’. So, eventually the label ‘race riot’ had two meanings: 1. members of a population group attacking members of another group, mostly whites assaulting people with non-white skin colours or different origins; and 2. disturbances by black and coloured people, destroying property and assailing the police. The acquisition of the second meaning also came from the US.

In the second meaning the extensive use of the label ‘race riot’ helped to marginalise specific population groups in Britain, particularly marking immigrants and their descendants who were perceived as a different race because of their skin colour. For example, the statement in the Morning Post in 1919 that coloured and white races cannot live together as equals because of insurmountable differences. Or the interpretation in The Times of the 1980 Bristol disturbances that stressed the large number of black youths estranged from society. And the insistence of The Sun and Daily Mail that black population groups bore responsibility for the 1985 disturbances. This confirms the findings of scholars like Van Dijk and Criado who have emphasised a prejudiced tendency in newspapers to classify black and coloured people as troublemakers.

To escape this bias, avoid further confusion, acquire more knowledge and gain deeper understanding, this article suggests redefining a ‘race riot’ in neutral terms as an incident of civil disorder involving two or more population groups perceived as races because of shared outward physical characteristics or cultural commonalities and resulting from tension or hostility between these groups.

References

Bell A (1991) The Language of News Media. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bingham A and Conboy M (2015) Tabloid Century. The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the Present. Bern: Peter Lang.

Chessum L (1998) Race and Immigration in the Local Leicester Press, 1945–62. Immigrants and Minorities 17, 36–56.

Connell K (2024) Multicultural Britain. A People’s History. London: Hurst.

Criado R (2005) Oldham’s 2001 Race Riots: A Critical Discourse Analysis of British and Spanish Newspapers. In: Carrió-Pastor ML (ed.) Perspectivas Interdisciplinares de la Linguïstica Aplicada. Volumen II. Valencia, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, 75-87.

Evans H (1972) Newsman’s English, London: William Heinemann.

Evans N (1980) The South Wales Race Riots of 1919. Llafur 3, 5–29.

Fairclough N (1995) Media Discourse. London: Bloomsbury.

Farrar M (2002) The Northern ‘race riots’ of the summer of 2001 – were they riots, were they racial? A case-study of the events in Harehills, Leeds’, paper delivered at the BSA ‘Race’ and Ethnicity Study Group Seminar ‘Parallel Lives and Polarisation’, 18 May 2002, City University, London.

Flett K (ed.) (2015), A History of Riots, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Griffiths D (ed.) (1992) The Encyclopedia of the British Press, 1422–1992. London: Macmillan.

Hilliard C (2022) Mapping the Notting Hill Riots: Racism and the Streets of Post-war Britain. History Workshop Journal93, 47–68.

Holmes C (1975) Violence and Race Relations in Britain, 1953-1968. Phylon 36, 113-124.

Kanol E (2010) An Analysis of Selected Factors Regarding the Race Riots in Britain. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/315579 (accessed September 2025).

Jenkinson J (2009) Black 1919: Riots, Racism and Resistance in Imperial Britain, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Keenan, H (2016) From Tulsa to Ferguson: Redefining Race Riots and Racialized Violence, thesis City University of New York.

Kibble M (2002) ‘The Betrayers of Language’: Modernism and the Daily Mail. Literature and History 11, 62–80.

May R and Cohen R (1974) The Interaction between Race and Colonialism: A Case Study of the Liverpool Race Riots of 1919, Race and Class 16, 111–126.

Miles R (1984) The Riots of 1958: The Ideological Construction of Race Relations as a Political Issue in Britain. Dissertation University of Glasgow.

Miles R (1984) Notes on the ideological construction of ‘race relations’ as a political issue in Britain. Immigrants & Minorities 3, 252-275.

Moran, M., Riots. Available at: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780190922481/obo-9780190922481-0006.xml (accessed September 2025)

Panayi P (1991) Middlesbrough 1961: A British race riot of the 1960s? Social History 16, 139-153.

Ray, V (2022) On Critical Race Theory. Why it Matters & Why You Should Care, New York: Random House Publishing Group.

Rowe M (1998) The Racialisation of Disorder in Twentieth Century Britain, London: Routledge.

Schofield C. and Jones B (2019) ‘Whatever Community Is, This Is Not It’: Notting Hill and the Reconstruction of ‘Race’ in Britain after 1958. Journal of British Studies 58 (2019), 142–173.

Solomos J (2011) Race, Rumours and Riots: Past, Present and Future. Available at: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/16/4/20.html (accessed September 2025).

Van Dijk TA (1987) Communicating Racism: Ethnic Prejudice in Thought and Talk, London: Sage.

Van Dijk TA (1989) Race, riots and the press. An analysis of editorials in the British press about the 1985 disorders. Gazette, 229-253.

Van Dijk TA (1991) Racism and the Press. London: Routledge.

Woods O and Bishop J (1983) The Story of The Times. London: Joseph.